Blood, Oil, and Topography: Why Geography Still Shapes Geopolitics

How systems thinking can help ask better questions about complex things.

On a bleak winter morning in 2022 Vladimir Putin ordered the tanks to roll across the Ukraine border. News media told us this was “Russian aggression,” that Putin was ego-driven to restore the Russian empire. First Ukraine, then Europe, they said.

Maybe that’s true. It’s hard to tell. Because missing in the flashing red chyrons was any context. Mainstream news framed a narrative, but offered no way to make sense of anything.

Russia spoke of “security concerns.” But what does that mean? How can a state with the largest nuclear arsenal have security concerns?

The news media arguments are framed in “good guy” versus “bad guy.” Putin is a dictator, they said. Prevailing views are linear and simplistically causal: B happened because of A. It makes for powerful headlines and is easily digestible, but does little to help understand events.

Are wars launched on a whim or do they emerge from systems under pressure?

Geopolitics is complex. It’s a system and is inherently a matter of constraints. The ‘geo’ part of geopolitics, the geography, remains underappreciated, yet it is the structure which bounds the system in which the politics takes place. Despite 21st century technology in communications and air travel and hypersonic weapons, geographical constraints remain: the mountain range is still improbably hard to pass, ocean access is a necessity to participate in global trade, and wide open plains affect security concerns.

It raises the question: Is Putin maniacal or is there a system that modifies his options?

Systems theory gives us a way to think about these questions, about the structural realities shaping political decisions, avoiding moral judgments and ideology.

Systems Thinking: Constraints, connections, and unintended consequences

Donella Meadows, a systems thinking pioneer, describes a system as a set of connected elements organised to achieve something. It consists of three things: elements, interconnections, and a purpose. Change one part and you affect the others.

Systems operate through stocks and flows. Stocks are accumulations: oil underground, water in aquifers, fish in a lake. Flows either increase or deplete them: extraction, replenishment, consumption. A city’s groundwater is a stock; rainfall and pumping are flows. The balance between them determines what’s available. Systems respond through feedback loops. When one nation builds missiles, another sees a threat and builds more, leading the first to raise the stakes again. This is a reinforcing loop, each action amplifies the next. Balancing loops work differently: a thermostat switches off when temperature is reached, stabilising the system.

Tragedy of The Commons

The tragedy of the commons is a feedback loop. Fishermen fish the lake. When they harvest in balance, the breeding rate of the fish stock matches the flow of the catch. But, when one fisherman takes more, others take more. Over time, the fish stock cannot replace fast enough. The stock decreases. Each fisherman continues to over-fish to protect his own catch. It becomes a reinforcing feedback loop. Though the feedback isn’t immediate. It takes time, and there’s a delay between over fishing and the breeding cycle of fish. Policy makers don’t see it until the stock is depleted. The lake, though serves more than the fishermen. Farmers draw water for irrigation, the city draws it for drinking and sanitation, and migrating birds find refuge and food. Each new element places stresses on the system, creates new feedback loops, and these all interact and affect one another. Pesticide run-off leaches into the groundwater, invasive species arrive accidentally through logistics activity. Environmental laws are passed, but fishing communities have left. Actions meant to solve one problem create others elsewhere in the system.

Delays matter. China’s one-child policy from the 1980s, enacted to curb rapid population growth, has seen unintended consequences two generations later. Not least, a skewed gender imbalance brought about from the preference for male children. Curbing population growth was a calculation based on an ideal population size, driven by fear of poverty and famine. Yet, deeply cultural was the preference for boys.

This matters for geopolitics because the structure of the system shapes behaviour. The lake cannot be moved. The fishermen need to eat. The farmers need water. Policy makers face constraints they didn’t create and cannot eliminate, they can only work within them. It’s not about good intentions or bad actors. It’s about the system’s architecture limiting what’s possible.

Geography functions the same way. It creates the physical structure, the immovable stocks and flows, within which political decisions happen. It’s a battle of constraints.

Geography: The structure of physical constraints

Much like the lake cannot be moved, neither can the mountain range between two nations, nor the navigability of a river system. These physical constraints bound the decisions of leaders.

Consider Brazil and the Congo. In Brazil, mountain ranges rise sheer just miles inland from Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo and rivers on the eastern seaboard run away from the coast. Waterfalls impede river navigability across the continent making costlier ground transportation the principal logistics option. In the Congo, the mighty river is fractured by the Livingstone Falls, 350 kilometres of brutal rapids just outside the capital, Kinshasa, cutting off ocean access for river barges.

Contrast this with Europe. The Danube is navigable along almost its entire length across ten countries. The Rhine cuts through Germany’s industrial heartland across flat plains to the North Sea. Since transportation by water is far cheaper than by land, geography hands Europe an enormous advantage absent in Brazil or the Congo.

Brazil: The constraint of distance

The agricultural heartland of Brazil, the state of Mato Grosso, sits 2,000 kilometres from the main port at Santos, near São Paulo. Over sixty percent of Brazilian commodities move by truck, a consequence of lacking a navigable river system from the heartland to the Atlantic coast. The World Bank estimates logistics consume 12-15 percent of Brazil’s GDP, compared to 8 percent in the United States. During harvest season, at peak activity, the Port of Santos chokes with massive queues and delays.

The cost and constraint of geography runs so deep it has a name: “Custo Brasil,” the Brazil cost. Any leader taking office in Brasília inherits this friction. The constraint shapes every infrastructure decision, every trade negotiation, every budget allocation, no matter who is in office or what party holds power.

Congo: When geography fractures the state

Across the South Atlantic, the Democratic Republic of Congo faces even more severe constraints. A massive country in the heart of Africa, over half of it covered in dense rainforest and rugged terrain. There is no fully functioning highway between Kinshasa in the west and Goma, a hub for mining operations in the east. That’s 2,500 kilometres. The DRC has just 3,000 kilometres of paved road total. In bad weather, much of the country becomes impassable.

One wonders if the Congo might be a very different place if its riches in the east could be floated down the river to an ocean port. Instead, the impenetrable rainforest makes infrastructure costs unbearable. This fragments governance itself. Kinshasa struggles to maintain security in the east because the east is logistically unreachable. Geography fragments the state physically, socially, and ethnically. There is no state monopoly on force. Power decentralises because it cannot be controlled centrally. Geography offers the conditions under which corruption and militia activity become the path of least resistance; rational strategies within the system.

Think of this as a reinforcing loop. The extreme geography of rainforests and rapids makes it impossibly costly to build and maintain the roads and infrastructure needed to control the east. Providing administration and security across the country, moving personnel and supplies to the eastern mining regions, becomes prohibitively expensive. So the government uses warlords and mining companies to run the region in exchange for bribes and a cut of the riches. The militias extract the wealth, the state loses revenue, infrastructure remains unbuilt, and the cycle reinforces itself. The rainforest remains operationally impenetrable.

Geography doesn’t cause the corruption. It places a constraint on the system, shapes the option set, and the system responds.

Resources: A constraint of flows

Resources are stocks. Oil underground, fresh water in mountain aquifers, minerals in the earth. The supply lines that move them are flows. Control the stock or the flow, and you control survival. Access to resources shapes national strategy: Congo’s cobalt and tungsten, Middle Eastern oil, Tibetan fresh water. When the flow is threatened, leaders act. The constraint is existential.

Imperial Japan: When the flow stops

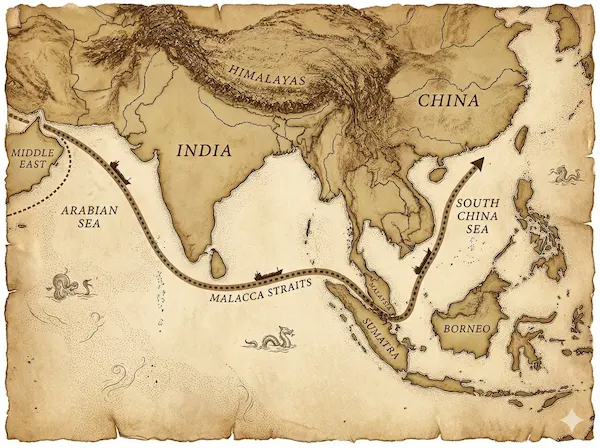

In 1941, Roosevelt cut off US and British oil from Japan. Japan imported 90 percent of its oil. Without it, the war efforts in China and Indochina would collapse within months. The constraint was binary: secure alternative supplies or face defeat. Japan invaded Southeast Asia to seize oil, rubber, and tin for its war machine, then faced the 3,000 kilometre supply line home.

Eighty years later, the players have changed. The fundamental constraint hasn’t.

China imports roughly 70 percent of its oil, a critical constraint for a massive industrial economy. Geography compounds the problem: China lacks abundant hydrocarbons, and its supply lines stretch from the Middle East across the Indian Ocean, through the Straits of Malacca, into the South China Sea. The Middle East still supplies about 50 percent of China’s oil, with another 15 percent coming from Russia. The Russian supply is growing. An advantage China has over Japan is a land border with a major energy producer. Although the vast majority of oil destined for China passes the Malacca Strait.

Strategy from constraints

This systemic constraint shapes Beijing’s infrastructure investments. The China-Pakistan corridor runs from Xinjiang to Gwadar, a stone’s throw from the Strait of Hormuz, reducing vulnerability through the Malacca Strait. China built its first foreign military base in Djibouti to project power along those very supply routes. Seen through the lens of resource flows, its South China Sea strategy, is about the system’s survival.

Fresh water tells the same story. Much of China’s fresh water originates in the Tibetan plateau. Control of fresh water is a long-term existential constraint shaping policy, regardless of who’s in power or what political system operates.

Singapore offers a smaller-scale version of the same dynamic. It relies on Malaysia for roughly 30 percent of its daily fresh water needs. The constraint forces Singapore to invest heavily in alternatives, like desalination to reduce dependence on a foreign source.

The pattern holds: when geography creates resource constraints, leaders respond. The response may vary in detail, but the underlying logic of securing the stock and protecting the flow, remains constant.

Neighbours: You can’t choose them

Geography locks you next to certain nations. You can’t relocate. The constraint forces calculation.

Malaysia and Singapore maintain largely cordial relations. Compare that to India and Pakistan; bitter adversaries since partition in 1947, fighting multiple wars over contested borders, both armed with nuclear weapons. The mutual resentment is a reinforcing loop: each military buildup justifies the other’s. The presence of nuclear weapons raises the stakes for the planet.

Brazil demonstrates how the same geography can create opposite constraints. The Amazon basin and vast interior that friction trade also provides security. The rainforest and vast distances act as a moat, making land invasion nearly impossible, and Brazil sits far from the world’s major conflict zones, an advantage unavailable to nations in Europe or Asia.

Across the northern plains of Europe, geography tells a different story. Flat, open terrain makes it relatively easy to move armies and supplies. Present-day Poland forms a natural corridor to Moscow. It’s position, having been invaded by Germany in recent memory and having Russia to the east, weighs on it’s leaders decision-making and considerations.

Looking westward

If you are sitting in Moscow, this is the geography you see. Over the past two centuries, Russia has been invaded from the west repeatedly: Napoleon in 1812, Germany in World War I, Nazi Germany in 1941. Nazi Germany killed over 20 million Soviet citizens.

The question becomes: does the geography influence Russian thinking on security? If so, how does it constrain the options?

A century before the current crisis, the “Great Game” pitted the British and Russian Empires against one another across the rugged plateaus of Persia and Central Asia. For the Tsars, the structural constraint was a desperate lack of warm-water ports; for the British, it was the geographic vulnerability of the land routes to India. These manoeuvres demonstrate that while ideologies and leaders change, the systemic pressures of the physical map remain constant across generations.

Geography doesn’t justify any particular action. It explains the structural pressure any Russian leadership faces. A different leader might respond differently in degree, but the geographic constraint, remains unchanged.

Borders and the inheritance of conflict

Borders, whether created by mountain ranges or drawn on maps by colonial powers, create their own constraints. Ethnic groups that existed long before those lines often find themselves split across modern nation-states. The borders of India and Pakistan, hastily drawn in 1947, cut through Punjab and Bengal, dividing communities and creating permanent tensions. Kashmir remains contested seven decades later. Pashtuns exist across the mountainous regions between Kabul and Peshwar down to Quetta, their ancient lands, regardless of the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

France and Germany fought three devastating wars between 1870 and 1945. The coal and iron rich industrial regions of Alsace-Lorraine, the Rhineland, and the Ruhr Valley sat between them. Geography made them neighbours and competitors. Only after World War II, with the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community, did the constraint begin to shift. They couldn’t move the resources or the border, so they changed the system governing access.

Each nation, each set of leaders across time, bears responsibility for securing their people against nearby adversaries.

Yes, we can cross mountains, but it’s still very hard and costly

An appreciation of geography as an immovable architecture of the geopolitical system lets us see beyond the headlines and nationalist rhetoric. We can ask deeper questions about the structural constraints shaping decisions.

This is not about excusing actions, labelling political systems as good or bad, or morally judging any leader. Geography is one part of an extraordinarily complex system, but one that is consistently overlooked and misunderstood. The impenetrable rainforests of the Congo, the vulnerable plains west of Moscow, the chokepoint of the Malacca Strait, these shape the options available to any leader in any political system. Overthrow the government in Iraq or Libya, the oil still remains under their earth.

When we understand this, we can step back from the immediate crisis and ask better questions: What constraints are evident in the system? How does geography limit their choices? What feedback loops are already in motion? What are the likely second-order effects of this policy?

These questions don’t predict what will happen. They help us think about what’s structurally possible and why certain patterns repeat across different leaders, different eras, different ideologies.

The geography remains. The constraints persist. The system responds.

Read more: my thinking

© 2025 think provocative. All rights reserved.